In May 1971, the American Psychiatric Association was bracing for trouble. The organization was preparing to hold its annual convention in Washington, D.C. The previous year’s convention in San Francisco had been disrupted by a militant band of gay activists. Strategically planting themselves in breakout sessions on sexuality, the protesters had successfully turned the academic event into a series of shouting matches.

Research on conversion therapy was booed, individual psychiatrists were branded as Nazis, and demands for representation were made clear. Against this backdrop, the APA had agreed that the 1971 convention would host the organization’s first gay panel — a panel made up of self-identified homosexuals, speaking about homosexuality. But the APA suspected this would still not be enough.

For him, their much-vaunted “compassion” is no compassion at all. It amounts to “a cynical agreement with Oscar Wilde, that the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”

This suspicion proved correct, as chief activist Frank Kameny worked with Washington’s Gay Liberation Front collective to mount another systematic disruption. On May 3, they moved in. Amidst the chaos, Kameny picked up a microphone and addressed the Convocation: “Psychiatry is the enemy incarnate. Psychiatry has waged a relentless war of extermination against us. You may take this as a declaration of war against you.”

Stripping away the pretense

In October of that same year, an IVP book received its first American printing, after its British debut in 1970. The main title was “The Returns of Love.” The subtitle on the dust jacket was “A Contemporary Christian View of Homosexuality.” But on opening the book, readers would find a different subtitle printed on the title page: “Letters of a Christian Homosexual.”

These “letters,” as explained in the introduction, were a literary device, crafted and arranged to record the author’s brutally honest struggle with unwanted same-sex attraction to his best friend. Part practical theology à la C.S. Lewis, part confession à la Augustine, they stripped away all the pretense and false hope that was stereotypically assumed to accompany a traditional sexual ethic. The name of the author, a young English Anglican, was given as “Alex Davidson.” This was not his actual name.

Fifty-odd years later, the book is long out of print, though stray used copies can still be found and Open Library has preserved a couple of rentable e-copies. But it exists firmly in the realm of the artifact — a work “of historical significance,” emphasis on “historical.” Yet in its time, it was considered a landmark work of evangelical Anglicanism. The highly influential minister John Stott singled it out in his own writing on homosexuality, saying no other resource had better helped him “to understand the pain of homosexual celibacy.” Nobody has ever successfully guessed the author’s identity, including two blundering Church of England history researchers who nearly credited the book to Stott himself.

From the text, one gleans only general clues that the writer is a young, well-read Christian layman, a typical representative of England’s “officer class.” He explains in the introduction that he doesn’t want to write with the voice of a minister dispensing prepackaged wisdom or a clinician dispensing “information.” He wants to write like a sympathetic friend, the sort of friend he suspects many of his readers might not have. He wants to actually do what T.H. White said he would have done, if he “had any guts”: to write a “sexual autobiography.”

A wounded protest

Whoever Alex was, he certainly had guts. This is hard to appreciate today, when even in conservative Christian circles, books in this general vein constitute an entire publishing niche and the writers promote them with their own names and faces. Some of these biographies are much grittier than Alex’s, including time actively spent in the writers’ respective gay scenes. Some of their writers are my friends. One could speculate about whether Alex would even have wanted to openly join them, given the choice in 2023. But in 1970, he didn’t have a choice.

This historical context lends the work a unique quality, setting it apart in style and substance from contemporary work. It uses the language of its time, including now-long-retired vocabulary like “queers” or “inverts” (the latter historically used to distinguish non-practicing homosexuals from practicing “perverts”). It predates cultural touchstones like the AIDS pandemic and the rise of the religious right. In general, the work is heavy on introspection and light on social commentary. Though, when Alex does turn his focus outward, he expresses a complicated mix of emotions. At one point, he unleashes a wounded protest that men like him are not all “pansies, bohemians, maniacs, etc.” — a protest that is distinctly Christian in flavor yet echoes uneasy old tensions that still divide gay men everywhere:

Here we are — there really are men like us, with a certain peculiarity in our makeup which is in itself no more morally blameworthy than left-handedness. We are not necessarily pansies, or bohemians, or maniacs, or lechers. Many of us do our best to lead decent respectable lives and to appear as normal human beings, and some of us succeed. And so long as our abnormal affections are never expressed in ways which are against the law, whether God’s law or man’s, the law speaks nothing against us. So why should an ignorant society? Why should a Pharisaic church?

Alex is also a man of his time in that he is still fundamentally heteronormative and still takes orientation change therapy seriously, though with clear caveats that it’s not a cure-all and hasn’t been much help in his own case. As a Christian, he gives these caveats a distinctly theological spin, challenging the idea that the truly regenerate Christian will be “delivered” from this temptation. He presents himself as walking proof that even the most earnestly devout Christian man has no guarantee of such miraculous “deliverance,” warning against a narrow reading of Scripture that will give other men like him false hope.

The map and compass

At the end of the day, the “software” or “hardware” question is immaterial to Alex. Whether he was “born this way” or it was acquired it through some outside influence, his “map and compass” — God’s revealed will in natural and special revelation — will point his next steps in the same direction.

Meanwhile, he’s not looking for special treatment or pity. He’s not interested in attaching himself to a victim group. He will be nobody’s mascot in nobody’s proxy war. “It’s such an easy way out,” he reflects severely, “to plead ‘I don’t know what came over me, your worship,’ ‘I must have had a blackout,’ ‘It’s my nerves,’ ‘It’s my genes,’ ‘It’s my upbringing’; anything rather than ‘It’s my fault.’”

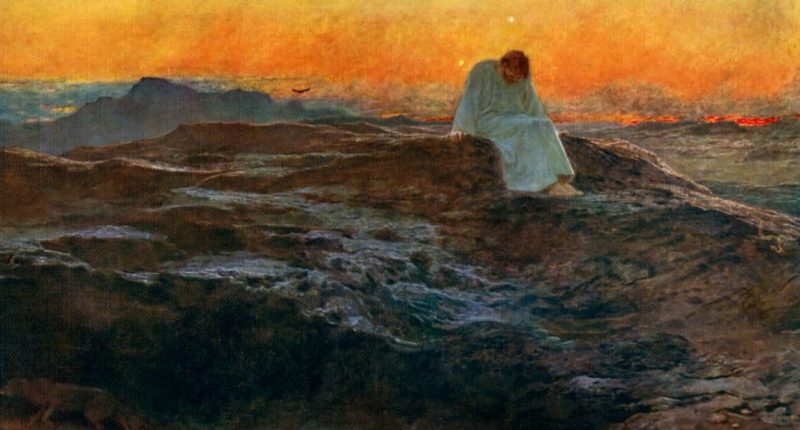

Christianity alone “offers a contrast, the narrow way of accepted responsibility,” a way that, by virtue of its very severity, is uniquely dignifying. “Not even I shall be able to plead ‘It wasn’t my fault, Lord, I was made that way.’ I’m a man, not a machine.” And in thus embracing his manhood, Alex takes up his cross and follows in the way of Christ, the perfect man of sorrows: “A crucified passion, like a crucified man, is a long time dying, and it dies hard and painfully. But crucified it must be. … The ‘flesh’ revives often enough, and from its cross cries out for something to satisfy it: ‘I thirst.’ Then let it thirst.”

Contra Sullivan

Of course, writers like Andrew Sullivan would strenuously argue the opposite. His essay “Alone Again, Naturally” makes an interesting counterpoint to Alex’s work. Doubtless, Andrew would pity Alex as a young man like he once was — at war with his “natural” self, repressing his emotions by retreat into an emotionless theological austerity. According to Andrew, a non-affirming doctrinal framework cannot even see men like Alex “as truly made in the image of God.” And so, by denying himself full sexual gratification, Alex is really denying his full humanity.

But Alex deserves his own voice in this conversation. And when speaking of the sort of progressive churchmen who would agree with Sullivan, he bluntly writes, “I don’t want that kind of care.” For him, their much-vaunted “compassion” is no compassion at all. It amounts to “a cynical agreement with Oscar Wilde, that the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.” However much a part of him may want to be accepted “as a sinner,” he will continue to “delight in the law of God after the inward man.” To the clergy who would argue that their way is the true way of Jesus, he would say this fails to understand the harmony of law and love:

God is Law, and he sets his standards fearsomely high; but He is also Love, and in Christ He gives grace and help so abundant that it is no-one’s fault but our own if we fail to measure up to those standards. Law and Love seem to move in opposite directions, but to such lengths do they both go that eventually they meet again on the other side of the globe. Because God’s reach encompasses the whole world of morality, however far His law requires me to go His love will be there to enable me. In the words of the old hymn, “the trysting place where heaven’s love and heaven’s justice meet” is the cross of Christ, but by the same token they also meet in the sinner who has been crucified with Christ; in him too the infinite demands of righteousness are fulfilled by the infinite resources of mercy.

One can only imagine how Alex would assess the state of the Church of England today. Perhaps someone should recommend this book to Justin Welby, complete with trigger warning.

‘Someone in daily nearness to love’

At the same time, Alex is not at all sanguine about the pain that can accompany his chosen path. He dismisses progressive “hireling” ministers, but he also struggles to find traditional ministers willing and able to understand him. He writes with heartbreaking candor about his longing for “someone in daily nearness to love.” Most painfully, he retraces his fumbling attempts to sublimate his unrequited attraction to the best friend on the other side of the “letters.”

We learn little about this friend except that he’s also a Christian and that unlike Alex, he has a history of homosexual hookups. Alex doesn’t hide the intensity of this “grand romantic passion.” The book’s very title, “The Returns of Love,” is a nod to the gay poet Walt Whitman, who referred to his poems as “songs” written out of unrequited homosexual love.

In a way, Alex sees these letters as his own baptized “songs.” His frustration reaches its highest poetic pitch in a chapter about his failed attempt to date a woman, whom he desperately wishes he could love the same way he loves his friend. It’s an unnervingly honest chapter, cruel and funny and tragic all at once. One could fairly argue it’s out of place in a work of practical theology. But then that’s part of what gives the work its oddly fascinating, unrepeatable quality. It is practical theology, but in a way, it’s also art.

In his more mature, reflective moments, Alex writes in a key of lament mixed with expectation: lament for all the questions that remain unanswered, expectation “that one day my sanctification here will end and I shall be glorified in heaven, and that under the hand of God the finished product will be a splendour for angels to marvel at.” This is not escapism. It’s faith — the same faith by which Abraham made his dwelling in tents, looking to the light of the city to come.

By the end of the journey, contra Andrew Sullivan, Alex has painted a self-portrait that is nothing if not deeply human. It’s a young man’s portrait, earnest and awkward, at some times unintentionally funny, at all times unblinkingly honest. And ultimately, it’s the portrait of a man who believes himself completely known and loved by the same God who bids him come and die: “‘Alex — sinful, hypocritical, embarrassed, homosexual Alex,’ He calls; and in doing so He demonstrates both that He knows all about me and that He still loves me in spite of it.”

“Listen, child,” he imagines God saying to him in an epilogue. “Listen, child — you who are by the Fall a sinner, yet still by creation a man, and now by redemption a saint: these are wonders I mean to declare before the eyes of the universe. Walk with Me through the wilderness.”

“Yes, Lord,” he answers.

This essay first appeared on Bethel McGrew’s Substack, Further Up.

Also Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celebrity News